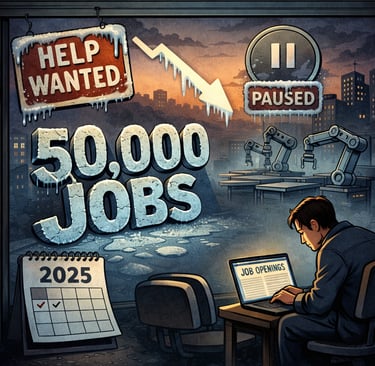

JOB MARKET COLLAPSE

Hiring slowed more than expected in December, capping off one of the weakest years for job growth in several decades and deepening the pressure on America’s affordability crisis.

The U.S. economy added just 50,000 jobs in December, down from a revised 56,000 in November, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Economists had expected 55,000.

Zoom out and the picture gets more sobering. For all of last year, the economy added only 584,000 jobs. Outside of recession years, that’s the weakest annual growth since 2003. And most of those gains came from just a few sectors. As Heather Long put it, this was essentially a “jobless boom.” Without hiring in health care and social assistance, 2025 likely would have shown outright job losses.

Revisions made the situation look even softer. Payroll estimates for October and November were cut by a combined 76,000 jobs. And January’s annual benchmarking process is expected to further reduce the totals. A preliminary estimate already suggests 911,000 fewer jobs were added during the year ending March 2025 than initially reported. Some economists now say the story may shift from “slow growth” to something that looks much closer to recession conditions.

Meanwhile, long-term unemployment is creeping up. In December, 26% of unemployed Americans had been out of work for 27 weeks or more. That’s a troubling sign. It suggests unemployment is becoming less of a short transition and more of a lingering condition for many people.

There were a few bright spots. Wages rose 0.3% for the month and 3.8% year over year, slightly outpacing inflation. That helps. But steady wage gains don’t mean much if hiring momentum stalls.

The slowdown became more pronounced after April. Roughly 85% of last year’s job gains occurred in the first four months. By spring, hiring cooled sharply. Policy uncertainty, including sweeping new tariffs announced that month, increased business caution. Companies already adjusting after pandemic-era overhiring began pulling back further. At the same time, firms redirected cash toward artificial intelligence investments, slowing workforce expansion.

Most industries either stagnated or lost jobs. Manufacturing and retail both shed positions, and seasonal hiring was weaker than usual. The only meaningful job growth came from health care, reflecting an aging population, and leisure and hospitality, supported by higher-income consumers who continue to spend despite broader economic strain.

What we’re looking at isn’t a dramatic collapse. It’s something subtler and in some ways more unsettling… an economy that’s technically growing but not meaningfully expanding opportunity. A low-hire, low-fire labor market feels stable on paper. But for people trying to break in, reenter, or move up, it can feel like the door is quietly locked.